I’m not expecting you to love Rocketman as much as I did. I’m assuming you won’t, for the same reason I don’t expect most people to love Stéphane Lambiel’s 2005-2006 free skate choreography or R.E.M.’s Fables of the Reconstruction as much as I do. It’s a good movie, although not objectively the best movie I’ve seen in the past week.1

Rocketman is, however, a movie that made me run home and start an off-topic blog post. I’m pretty sure the last movie that inspired such feelings was The Martian, back when I was writing on SportsBlog. It’s a movie that made me search up the This Is Elton John playlist on Spotify and bop to “I’m Still Standing” all the way home on a Red Line train full of Cubs fans. That’s because, in addition to all the other excellent things it is,2 Rocketman is a movie about creativity that made me want to create. Since my gift is not my song, but my short-form analytical nonfiction, I came home from the movie theater and fired up WordPress.

What follows after the “read more” break could be construed as spoilery, although no more spoilery than Elton John’s Wikipedia page, which I recommend reading before you see the film anyway.

It’s no earth-shattering revelation that a biopic about a pop star is a film about creativity. But Rocketman‘s plot structure has more in common with a superhero origin story than with most biographical narratives about exceptional people. Most biopics put forth the comforting but possibly destructive fiction that prodigies are a lot like the rest of us. Rocketman does the opposite, constantly reminding the viewer that John’s musical talents are so extraordinary that they cross into the uncanny, the Hated and Feared. Early in the film, a preteen Elton auditions at the Royal Academy of Music and stuns the judge by flawlessly recreating the difficult classical piece that she was playing when he walked in – and stopping in the middle, because he can only play the section of the piece that he heard. Later, Elton’s lifelong collaborator, Bernie Taupin, hands him a sheet of lyrics and heads to the bathroom for a shave; by the time Bernie returns, Elton has noodled his way into a fully formed hook, verse, and chorus. The film frames both of these incidents as amazing but unnerving, emblematic of how Elton’s talents contribute to his overall strangeness.

That quality of strangeness is what defines Rocketman‘s vision of Elton. Deep into the film, Elton addresses it directly, telling his addiction support group that he’s learned to embrace being strange. The film acknowledges, bravely and sympathetically, that John is charismatic because he’s a weirdo, popular because he breaks the expected rules of pop stardom in ways that make him less relatable. Rocketman makes no attempt to convince the viewer that Elton is “just like us,” but instead leans into the many ways he is different from the people around him. He’s warm and sociable enough to make his way through the world, and that makes his oddness magnetic.

For all that Rocketman gave me permission to regard its portrayal of Elton as a specimen rather than a mirror, I saw plenty of myself in him. The real-life Elton John has been one of my queer icons since I saw the “I’m Still Standing” music video when I was a bespectacled, gender-nonconforming preschooler. As the lights came up over the closing credits of Rocketman, the friend I went with asked me what I thought, and the first words out of my mouth were, “It’s nice to see my gender represented on screen.”3

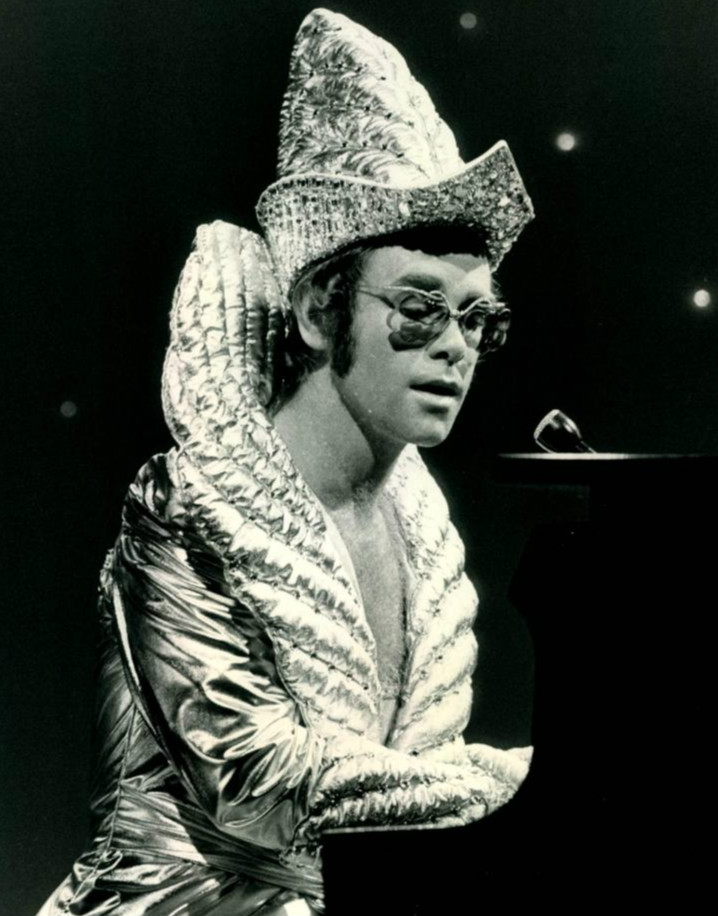

It’s especially refreshing after this well-meaning but troubling New York Times article on “rejecting the gender binary,” which insists on identifying all of its non-binary subjects’ assigned genders at birth and generally paints people like me as struggling, suffering, and needing lots of hormones and surgery to feel better. I’m sure that framework helps some non-binary folks, but I don’t feel like I’m rejecting gender by representing myself honestly, any more than I’m rejecting handedness by being ambidextrous. Elton John has been celebrating his genderqueerness since a much more dangerous time, in ways that challenge both masculinity and femininity without rejecting either. His gender is a Dodgers uniform encrusted in sequins, a Bob Mackie jumpsuit that reveals a bramble of chest hair, a dangling pearl earring that frames a scruffy face. I went to the movies with my hair freshly cropped short and dyed platinum, wearing a pair of shiny silver dress loafers and this t-shirt. This is, I will emphasize, my Sunday-afternoon-at-the-movies get-up. I’m pretty sure the real-life Elton John doesn’t identify as non-binary, but I think he’d be pleased to learn that his specific brand of gender nonconformity helped me see my own genderfluid flamboyance as joyful and legitimate.

The depiction of queerness feels all the more real because Rocketman is deliberately unreal. It’s a biopic that trades on our knowledge of how the genre works, and then messes with that knowledge to reveal the problems with taking a biopic at face value. It’s not directly punching Bohemian Rhapsody in the mouth, but it’s looking over its sequined shoulder and blowing a shady kiss.4 Rocketman establishes up front that it’s not even pretending to tell the objective truth. The opening sequence shows Elton gliding into an addiction support group meeting. He’s dressed in an orange Bob Mackie-esque jumpsuit bedecked with crystal-studded flames, a matching hood with devil horns, feathered wings, and rose-tinted heart-shaped glasses. This is how Rocketman establishes its narrative ground rules: take nothing literally, and everything representationally. It’s not only an effective unifying device, but shrewd protection against anyone who might claim that the film is biased or inaccurate.5

To make sure that we never mistake Rocketman‘s version of events for objective truth, it’s straight up a jukebox musical. The first number begins with a five-year-old Elton singing “The Bitch Is Back,” setting the tone with adorable impropriety. Characters break into song mid-dialogue with no concern for chronology, which is an effective way to narrate the life of a person who thinks in music. The film implies that John’s songs were always within him, waiting for their moment. The placement and arrangement of the songs also highlight Bernie’s presence in them. It becomes clear, for instance, that “Tiny Dancer” voices Bernie’s experiences with women on the road, not Elton’s. It’s a beautiful sequence, largely a tracking shot of Elton strolling through a party full of heterosexual pleasures, the guest of honor alone in a crowd.

That scene is far from the only one in the film to use fantasy and metaphor as mirrors for the realities of queer experience. But its sex scene between Elton and his manager/boyfriend, John Reid, stands out for its unapologetic realness. The camera pulls in close on chests and crotches, lingering on the two men fumbling with each other’s belts. The scene is awkward, hungry, and suffused with affection. It’s probably nothing like the real first time Elton and Reid had sex, but it reads like somebody’s plausible first time. And despite the fact that the film’s director, Dexter Fletcher, is straight, the camera maintains a queer gaze that doesn’t feel like it’s filtered through straight perceptions of gay sex. Rocketman is real about exactly the things it needs to be – I could write a second blog post about its portrayals of addiction and of the friendship between Elton and Bernie – which helps it earn its fantasy elements.

If Rocketman is shamelessly, nakedly direct about anything, it’s a love for Elton’s music. It delights in the small touches: the white space of silence after the opening chord of “Bennie and the Jets,” the leaps to falsetto in “Crocodile Rock,” the off-beat triplet figures that twirl the ends of lines in “Your Song.” The film has fun with Elton’s arena-filling pageantry, but it shows how perfect his compositions are when you put them under a microscope, too. Unlike a lot of other jukebox musicals and musician biopics, Rocketman doesn’t assume that you already know how great Elton’s music is. Instead, it does the hard work of proving why the songs are as great as they are, and leaves you with a deeper appreciation of them.

And the music is great. In my lifetime, it has never been cool to be an Elton John fan. But you know what’s cooler than being cool? A piano line that jangles and transforms around an indelible hook. Seething punk-rock rage delivered in such a sweet pop package that you finally read the lyrics to “Goodbye Yellow Brick Road” sometime in your twenties and spend the next week trying to unspin your head. Even if you didn’t spend many hours of your childhood in the backseat of your dad’s car listening to The Very Best of Elton John, the songs are both more familiar than you realize and much more daring than you remember.

They’re also more influential than they get credit for. I’m fond of saying that my taste in music lives at the corner of David Bowie and Prince, but the Vampire Weekend and Kishi Bashi songs I’ve been bopping to this summer have way more in common with Elton’s music. And that’s just the stuff that passes for indie rock. Elton didn’t invent glittering pop weirdness – Rocketman wisely cites Liberace and Little Richard, as well as The Beatles – but he created a template that’s been taken up by every generation of pop star that followed him, from George Michael to Tori Amos to Lady Gaga.

So I loved Rocketman, but I’m not sure that’s a recommendation. The things about it that resonated with me aren’t universal, and I’m the kind of film viewer who had to give up on Roma because it kept putting me to sleep. But the purpose of this blog, beyond trying to sound smart about ice dance, is to give myself a place to take things apart to figure out why I like them. Rocketman is even more satisfying now that I’ve dismantled it, which probably means it’s a fantastic movie. It will, at the very least, leave you with a head full of song and the desire to sparkle.

- That would be Sorry to Bother You; I recommend leaving this tab open, blowing your mind with that, and coming back to this post when your head stops spinning.

- This post will focus solely on the excellent things. Rocketman has some notable construction and script problems, all of which I will be ignoring in this blog post.

- She replied, “You don’t have as much fur,” to which I responded, “You’ve never noticed the giant leopard-print Muppet of a vintage faux-fur coat in my front closet? I don’t wear it that often. Maybe I should wear it more.”

- It might be throwing that shade deliberately. Just before directing Rocketman, Dexter Fletcher stepped in to finish directing Bohemian Rhapsody after Bryan Singer was fired.

- It also shields the film from how mundane the literal truth can be, a persistent problem in rock documentaries. Another thing I watched this week was David Bowie: The Last Five Years, which posthumously managed to make Bowie boring. Dying rock stars: they’re even less interesting than dying normal people.

One thought on “Pop Songs for the Gleefully Strange: Why I Love Rocketman”