The Challenger Series kicked off this week with two simultaneous events – the Lombardia Trophy in Bergamo, Italy, and the US International Classic in Salt Lake City – and we are officially in peak skating season. It feels weird to say that with a few days of summer left in the Northern Hemisphere, as the program music on the live streams compete with my air conditioner humming in the background. But the majority of top skaters now begin their seasons with a Senior B or two, making the calendar more crowded for determined fans in September than in December. This is not great for those of us whose jobs finally get quiet when the weather gets cold.

Maybe this is why, rather than attempting to recap my favorite highlights from Lombardia and the US Classic, I am sticking my nose in a flame war about proposed ISU scoring changes that, if they are ever enacted, will be drastically watered down. It’s definitely why this post has graphs in it. (I considered running linear regressions but stopped myself short of true insanity.)

The proposed changes, as detailed in this IceNetwork article, range from reasonable and necessary to abjectly ridiculous. Here’s an overly reductive rundown:

- Reduce the base values of the most difficult jumps – especially jumps like quad flips and quad lutzes, which had never been attempted when they were assigned point values.

- Reduce the length of the men’s and pairs free skates to four minutes, and reduce the number of permitted jumping passes in a men’s free skate from eight to seven. This change has already been approved, and I am shaking my tiny fist at it, as are Kori Ade and Brian Orser. Top coaches are frustrated that these new policies are being touted as ways to improve artistry, because making programs shorter decreases the opportunities to build musicality and storytelling into choreography. I agree with this, and I’m also annoyed because stamina is, and should always be, one of the abilities that makes an athlete successful in the free skate. My inference is that the motivations are financial and logistical: shortening the programs is a way of making competitions shorter and therefore cheaper to run. Men’s and pairs events do tend to drag late into the night, but that doesn’t stop me from opposing how these changes are likely to impact the sport.

- Create more granularity in the grades of execution, so it’s possible to earn as much as +5 GOE, or lose as much as -5 GOE, for a technical element. This is the change I’m happiest about, because I have seen Maia and Alex Shibutani do twizzles, and because I am a statistics nerd who prefers appropriately sensitive rating scales.

- Award separate Olympic medals (and, likely, also separate medals at ISU championship events) for short “athletic” programs and long “artistic” programs, in addition to an all-around medal. Possibly, there would be gradual movement toward treating these as separate disciplines. I don’t think this is likely to happen – at least not as proposed – but it’s a reminder that there’s a vocal contingent that would rather just sign up for a jumping contest. I’m all for a jumping contest as a separate competitive event, perhaps with a format similar to the Aerial Challenge that the Broadmoor Skating Club has been hosting for the past few years.

As a fan, my first instinct is to trust my personal feelings on these matters. But I’ve spent the past couple of weeks learning how to get my statistics software to make elegant box plots and legible frequency tables, and dipping into Edward R. Tufte’s The Visual Display of Quantitative Information, which apparently is a book you read in college if you are not an English major. As a result, my second instinct is to throw a bunch of math at this, partially to discuss what kinds of scoring changes really would have a positive impact on figure skating, and partially to balance out the fact that I’ve already devoted plenty of blog space to the men’s skaters whose performances I most want to write about this week.

What I took away from most of my statistical wrangling is, revaluing jumps won’t change much. I recalibrated the scores for a number of athletes who competed this weekend, and the results remained the same. Deniss Vasiljevs tends to earn higher PCS than Brendan Kerry, but even with Kerry earning a couple of points less for his more difficult jumps, he would have beat Vasiljevs handily for bronze at the Lombardia Trophy.

I think Timothy Dolensky is a more aesthetically pleasing skater than Max Aaron or even Nathan Chen, but Dolensky’s multitude of technical errors dragged down his components score. A slightly fairer accounting on the PCS side wouldn’t have rescued him from a 6th-place finish under the circumstances, and his technical totals still didn’t come close to those of the athletes who placed ahead of him. My overall appraisal of the scoring changes – and again, I’m thinking as a professional stats nerd here, more than as a fan – is that their effect on the sport will be modest.

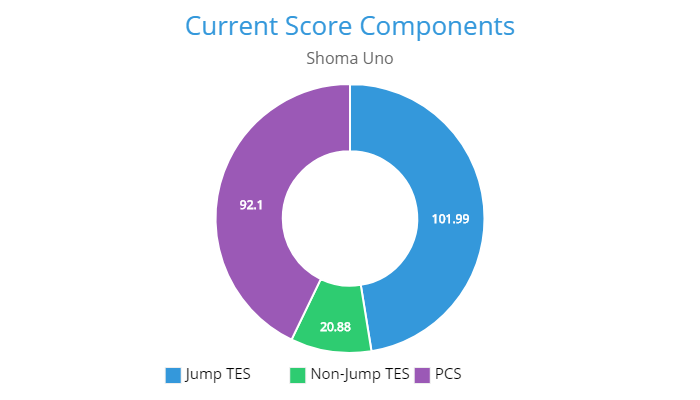

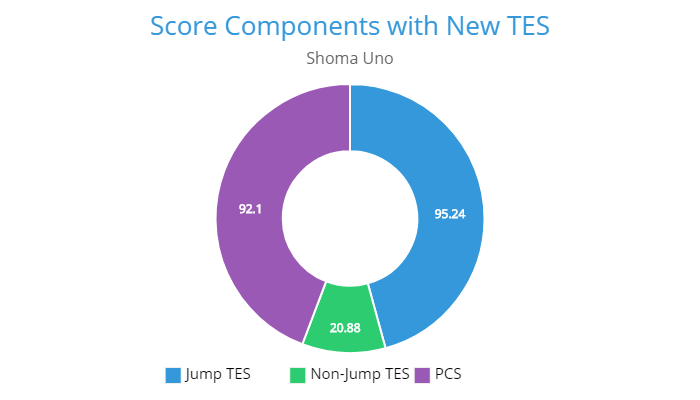

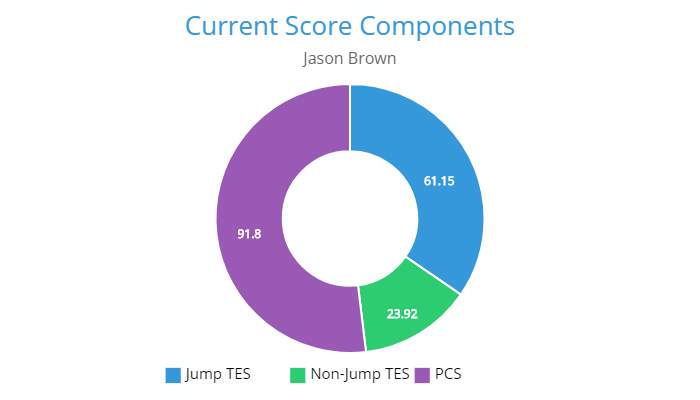

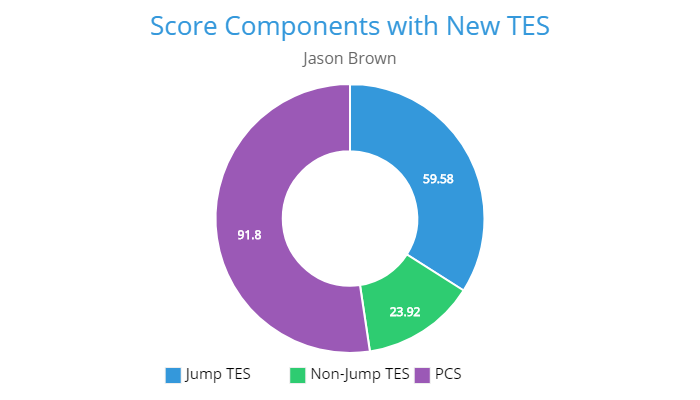

To illustrate this, I compared Shoma Uno’s and Jason Brown’s free skate scores at the Lombardia Trophy, both under the current scoring system and using the revised jump values. I left everything else the same: grades of execution, values for non-jump elements and double jumps, and program components scores. (It would have been nice to be able to test how the 11-point GOE scale will impact scores, but that would have required me to read the judges’ minds, so the current 7-point system stays.) It should come as no surprise that Uno still beats Brown by an enormous margin in the free skate, even with his quads worth slightly less. Under the current system, Uno earned 214.97 in the free skate, and Brown earned 176.87. Adjusted for the lower jump values, both of their free skate scores go down: Uno gets 208.22, and Brown gets 175.30. That’s still a blowout, but the margin is smaller: Uno now beats Brown in the free skate by 32.95 instead of by 38.10.

Where things do get interesting is in the ratios of how much their different strengths impact their scores. With the new, lower technical values, Uno’s high PCS do matter a bit more: they’re now 44.2% of his score instead of 42.8%. If the goal is to create better parity between technical and components scores, the re-valuing will accomplish that, albeit modestly. It’s possible that for a well-rounded athlete like Uno, who already earns high components scores (and, in my opinion, deserves them), the percentage difference would be statistically insignificant, but I’ll need more scores from more competitions to run the kind of significance tests that will confirm that hunch.

Things get more interesting when we look at how the proposed scoring changes will affect Brown, an athlete known for earning high scores on the strength of his components and execution. Uno, like most top skaters, earns almost half of his points from jumps alone, whereas at Lombardia, Brown’s jumps accounted for only about a third of his free skate point total. What’s remarkable is that with the new scoring in place, not only does Brown’s free skate total hardly budge – it goes down only 1.57 points, a reduction of less than 1%, as opposed to Uno’s change of about 3% – but the ratio of components to jumps doesn’t change much. This seems to be what the ISU intended: athletes like Brown, who rely on artistry, are rewarded for this approach.

Brown is a player in the one major change to this weekend’s results that the jump revaluation would bring about. At the US Classic, two American men earned higher overall scores than Brown did at Lombardia, and both of them did it with a quiver full of quads. Like Uno, Nathan Chen won easily, although unlike Uno, he skated conservatively, attempting only one quad in his short program and two in his free skate. Revalued jumps would have brought Chen’s score down a few points, but they wouldn’t have stopped him from winning the event by a tidy margin, or from becoming far and away the highest-scoring American man of the weekend. And deservedly so – a couple of technical errors didn’t detract from Chen’s most engaging artistic performance to date, with high components scores that reflected his growth.

Max Aaron, however, is another story. His overall score beat Brown’s, but by a slim margin of 1.68. I recalculated both skaters’ scores with the new, lower jump values, and in this case, it’s enough for Brown to pull ahead. Since the revaluation doesn’t impact Brown’s score as much, his new total becomes 257.60. Aaron – who landed five quads at the US Classic, three of them beautifully – takes a much bigger hit under the revaluation, especially because his PCS were far lower than Brown’s. Aaron’s overall score shrinks from 261.56 to 255.42, enough for Brown to pull ahead as the weekend’s second-best American. Brown beat Aaron by more than 11 PCS points in the free skate, a reflection of Brown’s superior interpretation and skating skills as well as Brown’s far more taxing choreography. If the goal of the revaluation is to give artistically adept athletes like Brown the edge over big jumpers like Aaron on a day when all other things are more or less equal, then it does its job.

The most interesting math problem arising from this weekend’s men’s events, however, centered around the two highest program components scores. Shoma Uno beat Jason Brown by almost 40 points in the free skate, and nearly all of that difference was in technical elements. On the components end, Uno edged out Brown by only 0.30, and both earned more than 90 points for components, a rare achievement at this point in the season. For all intents and purposes, the Lombardia Trophy judges threw up their hands and called it an artistic draw. Nobody else came close there; Deniss Vasiljevs’ components score was the third highest, and almost 12 points behind Brown. Chen, whose PCS were highest at the US Classic, trailed behind both Uno and Brown by about four points on his second mark.

At first, I questioned whether the two skaters really had tied, from a performance standpoint. When I’d watched the event live, Brown had stood out to me as the more accomplished artist. He’s had a few more years than Uno to develop his style and presence, and he has a preternatural gift for adapting to the mood and narrative of his music. Brown also navigates one of the most challenging pieces of choreography we’re likely to see this season, packed with sweeping flexibility moves and tricky turns that force him to maintain his momentum and balance when he’d rather be setting up for his next jump. This program has a little more breathing room than some of Brown’s past free skates, with more built-in opportunities for him to recover his speed. He also had to patch over a couple of wonky jump landings. The real irony is, this wasn’t Brown’s best showcase of his skating skills or interpretation, but Brown on a so-so artistry day is better than almost anyone else in the sport.

The problem with Uno, in terms of components, is that his finest qualities don’t come across on video. The tight frame of the camera makes his speed and ice coverage look less impressive, and it erases the impact of this small, shy man’s talent for filling a rink with his presence. Therefore, I have to assume that what comes off as a cautious and subdued performance was far more dynamic in person. What doesn’t disappear is Uno’s growing confidence in responding to his music with his face and upper body, as well as choreography that gives him more chances to show off his edges and core control than ever before. Next to Brown, he looks like an emerging artist rather than an established one, so I watched him again right after re-watching Nathan Chen. From that vantage point, it’s clear that compared to the other big jumpers of his generation, Uno is the most sophisticated performer. Chen is catching up in that respect, so Uno needs to watch his back. But for now, Uno has the advantage, and the ISU has all but assured that his performance ability will matter even more in the future than it does now.

I think re-balancing the artistic/technical with lower jump levels is a fine idea. Also, adjusting the GOE makes sense. The idea of separating things into a technical and artistic program reminds me of professional competitions in the 90s and makes me want to die. What makes skating so wonderful is the blend of athleticism and artistry. I hope the ISU realizes that. Shorter programs also seem like a silly idea but it doesn’t hurt my soul as much.